Skin Phillips interview

21.10.2024

We caught up with legendary Welsh photographer Skin Phillips for a conversation about his illustrious career, spanning five decades. His retrospective exhibition at Glynn Vivian in Swansea, Skin Phillips, 360°, runs until January 05 2025, and is well worth a visit.

Photography by Skin Phillips, courtesy of Glynn Vivian.

Interview: Genualdo Kingsford.

Portrait & exhibition documentation by Polly Thomas, courtesy of Glynn Vivian.

Magazine scans by Science Versus Life.

Special thanks to Jodi Moss.

When did you start skating?

I first started skating in about ’68, when the first wave of clay wheels came through here (Swansea). Because it was a surfing town, kids were always breaking up rollerskates and making skateboards out of them. When the ’70s thing came along, this shop called Dave Friar (Surf Shop) actually imported the urethane wheels, so we had all the new stuff quite early. I was just swept away in that ’70s wave. I stopped for a little bit in the late ’70s, and then started again when I got the camera in ’82. That was when it really took off again. I’ve rolled all my life really, on and off.

Did you surf as well?

I tried to surf, but I couldn’t really afford, it so I started bodyboarding and doing water photography. That’s how I started photography, shooting surfing and a little bit of skateboarding. Swansea has a massive surf scene. Gower has really good waves, so loads of people come here for the surf.

How did you get into photography?

I was a bit of a birdwatcher, so I knew what optics were through binoculars. A friend of mine had an Olympus Trip. I was about 15 when I saw that, and he was talking about aperture and shutter speeds. There was a teacher at school who saw something in me. She lent me a camera and I started shooting photos in school. I took an O-level (in photography) and got access to a darkroom, then I built a darkroom (at home). I couldn’t get into college; I just learned from going into shops and going to the library every day. I don’t think there’s an easy road to learn photography – it takes a while to get good at it. I wanted to become a photographer for a long time. It was just trial and error, but there were rewards in it, seeing the work.

Tell us more about shooting surfing.

I couldn’t afford a telephoto lens, so I bought a camera housing when I was 18 and did water photography, but my god that was gruelling. It was cold; it was hard to get the shot. I did that for a long time, then I got battered one time in France and that put me off. I got myself in a situation, got scared and stopped doing it. I wasn’t making any money doing it either, so after that – that was around ’89 – I started doing more skateboard photography.

Were your surf photos published?

Yeah, here and there. I had this famous spread of Carwyn Williams in Surf Scene back in ’87, maybe ’86. Even when I was getting published, I wasn’t getting paid. Back then you just sent a photo of your mate in. Some people were making a living out of it, but I couldn’t monetise it at all. In (skateboard) photography I had TLB (Tim Leighton-Boyce) and Grant Brittain, who really helped. In surf photography I never had anyone at a magazine or anyone who really helped in any way, so I was a bit more on my own, you know?

Interesting. What sort of skateboarding did you shoot at first?

Just ramp stuff, really. We had these really shoddy homemade ramps. We’d just jump from one to the next, and they got better each time. We were looking at all the American magazines and videos. We had the ESA (English Skateboard Association) comps three or four times a year, so I was shooting all the British scene at that time, around ’83, ’84, ’85. We knew everyone. Back then, the ESA was a real thriving tiny little community. There were more vert skaters, but street skaters and freestylers as well. We were kind of in the scene, even though we were on the peripheral. And then in ’84 I went to Münster and saw Gonz (Mark Gonzales), Lance (Mountain), (Steve) Caballero, (Rob) Roskopp… that was an eye-opener really early on.

Were you shooting for UK magazines during this period?

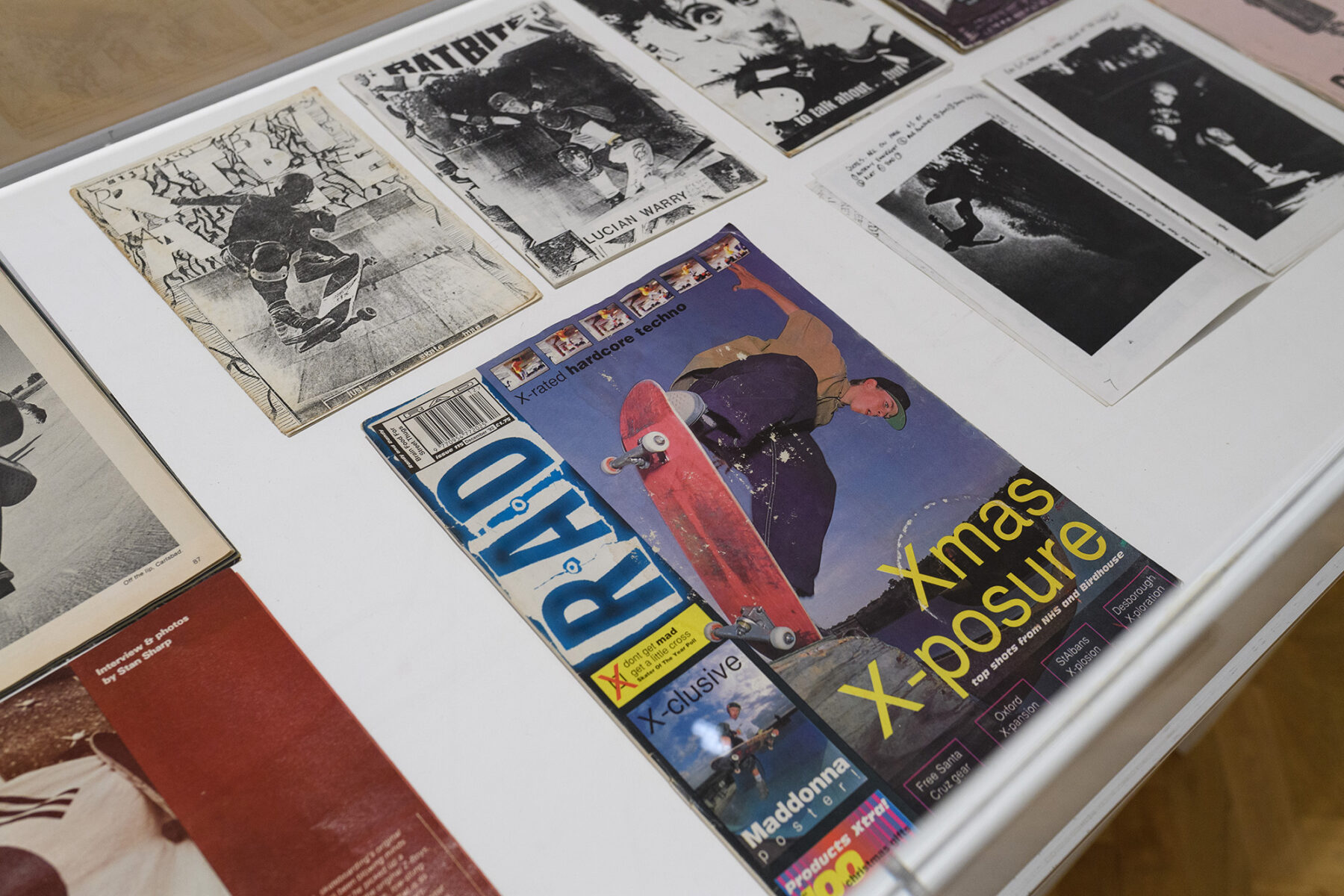

No, just for zines. I didn’t actually get a photo published ’til maybe 1990 or ’91. My friend Twiss (Enright) – who was an early skateboarder in Swansea – started a zine called Rat Bite in ’82. We’d do these perky little zines that were actually pretty good – they’d get published in Thrasher, in the zine thing they did. Twiss and Tomsk (Ian Thomas) were really connected to the American scene, so we had a good circle of friends. Doing those zines was doing everything – like typing, going to the shop to get them printed, cutting them up, collaging – so that was actually an early editorial experience. We’d do two or three a year, maybe more. I got more into that and we did these bigger surf / skate zines with 50 or 60 pages. It became a constant thing that I was doing, which was good.

What sort of quantities were you making?

Rat Bite would be 15 or 20, and then the other ones would be like 60 or 70, so it was all really small, but we would send them away. Zine swapping was a good way of communicating. You’d connect with people over your zine. That used to be quite a big thing in skateboarding. It seemed like in the ’80s, everyone who skated had their own zine. But Rat Bite wasn’t mine, it was Twiss’s. I was just a photographer.

Moving forward a bit, do you remember your first published photo in a magazine?

Yeah, it was a photo of Pete Dossett in Crantock, in a secret ramp in a barn. I think he was doing a japan air. That was in a R.A.D. photo annual.

Do you remember how that felt?

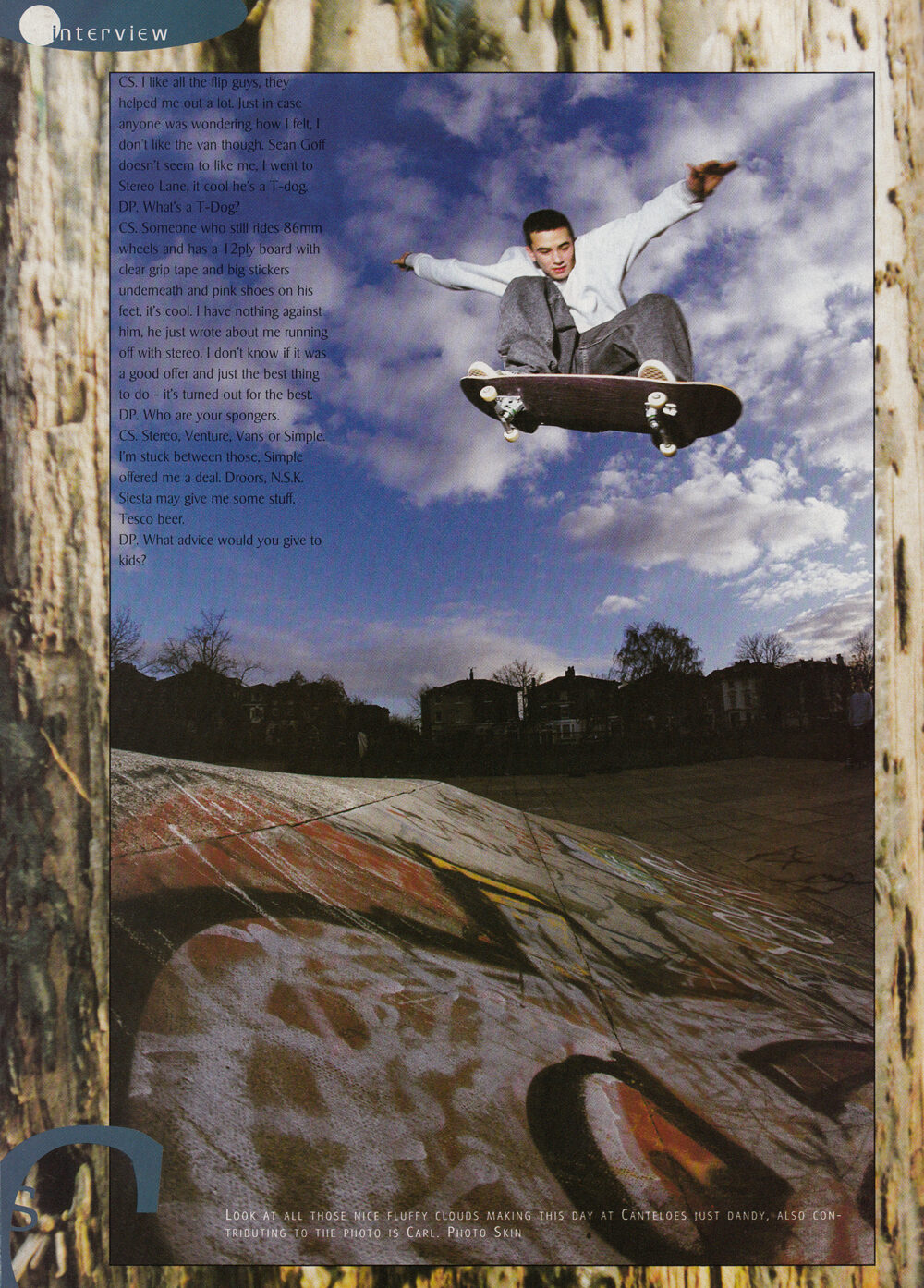

Oh, brilliant. That was amazing because it was the photo annual, so the paper was all lush, it was all glossy. It took a long time to get published, but after that, I got a Tom Knox interview done and I started putting packages together for Tim: contest reports, this and that. Over a year and a half, it went quickly for me at R.A.D. I became more of an editor there, as well as a photographer. I was going up to see Tim maybe once every two months, so we’d see each other quite a lot. I didn’t get anything published in Transworld until ’94, although I sent photos to them for like 10 years. I could never crack that one, but that worked out in the end. The early ’90s was really when it took off for me. I bought this nice fisheye that everyone was using, and that was night and day from the old stuff I was using. After the equipment got better, the photos instantly got better, and I started getting published quite a lot, almost straight away.

Aside from the zines, what kept you motivated to keep going during those years before you started getting published?

Work. I was a qualified chippy. I could paint houses, do all sorts of stuff, so I always supplemented everything with side-jobs. And then I think travelling kept me going a lot. That was my main thing. I went to Australia, America… The motivation was to keep going places and seeing skateboarding. It was just a really good fun time, going everywhere with your friends, travelling. We were always saving up to do that, whether it was a trip to France or a weekend away, so there was always something to look forward to and get away to.

Tell us about the Morfa ramp in Swansea.

The council started backing us in about ’84. We built one ramp in Underhill Park that lasted a weekend, then got torn down. We did this other ramp in West Cross that was based off Mountain Manor, which was really good. That lasted maybe a year or two before someone burned a hole in it, so that was derelict. Then we got the funding to build the Morfa ramp. We started that in ’88. It had 10 and a half-foot transitions, a foot and half of vert and it was 32ft wide. It was just this monster of a ramp. I put it together with my dad, and Arwyn (Davies) helped out. It took a summer to do, and then we had the British championships there, and the next summer the Powell team came. It just took off. People came from everywhere to ride it because it ended up perfect. Oh my god, the pros that came down… they would just blaze it. As a spectator, it was amazing to watch.

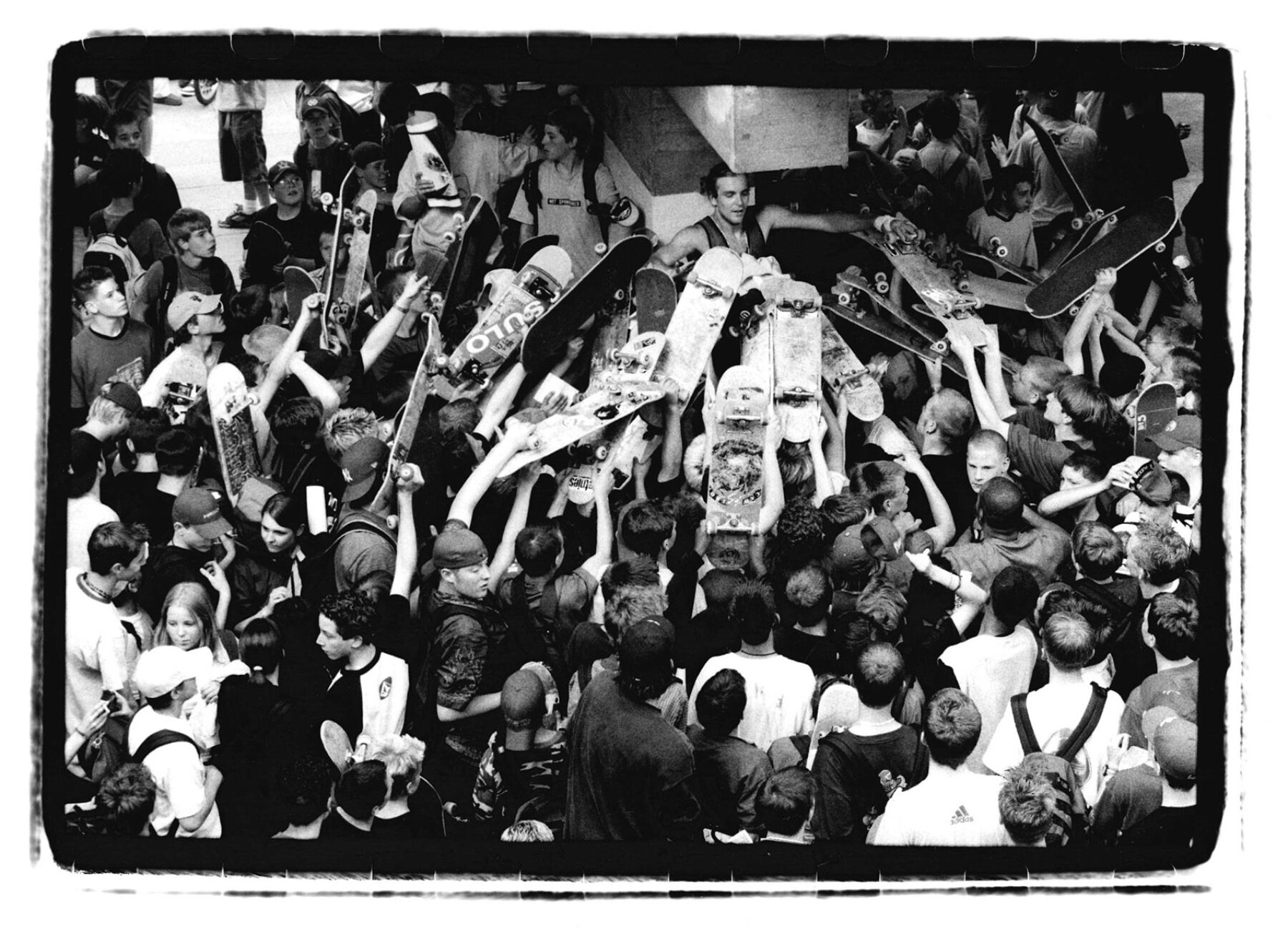

There’s a photo of Tony Hawk there in your exhibition at Glynn Vivian, skating in front of a big crowd of spectators.

Yeah, that’s from the second (Powell Peralta) demo with Lance (Mountain), Tony… I think (Mike) Manzoori was there as well. The year before – ’89 – Cab (Steve Caballero), (Mike) McGill and Tommy Guerrero came. All the ams came as well; there was a big crew. That was amazing. Those Powell demos were a really big deal back then. We had the European championships there too. People came from all over Europe for a long weekend and luckily, every time we did these things, we had good weather. Except one time, Plan B came down and it was rained off. We took them down to the NCP car park and they did a little flatland demo over a puddle. It was Rick Howard, Colin McKay, Danny Way and Mike Carroll (laughs). There were like eight people watching them; it was pretty funny.

You mentioned before that TLB was an important figure in your career. Can you talk a little about your relationship with him and how he helped you?

He did so much for me. Tim helped with the photos, he helped with processing – I’d go up and do all the black and white with him. He also helped me with some stuff, money-wise. The payment from the R.A.D. articles was a lot of money at the time. You’re talking £400-500 for a story, which was a month’s work down here, so it was quite a lot. Tim had his office in Camden and an apartment in Clapham, and we’d go and stay there. Simon (Evans) would be there, Gavin Hills, all that lot. He was the managing editor, so he dealt with everything. To see all that, like a one-man show, bringing up such a groundbreaking magazine… But he kept it young and right by letting everyone else get involved. He was so encouraging; he would never lose his rag with us. He was just an awesome boss, and an amazing photographer too.

He is. Did you manage to get to the R.A.D. exhibition in London?

Yeah. It was amazing to see Tim, Wig (Worland), Mike (John) and everyone again. Back then Mike was a big contributor, and Paul Sunman, but he (TLB) was also getting stuff from Spike (Jonze), (Todd) Swank, Grant was sending stuff, so he was corresponding with the best of the American market as well.

Who were some UK skaters you were shooting when you were working for R.A.D.?

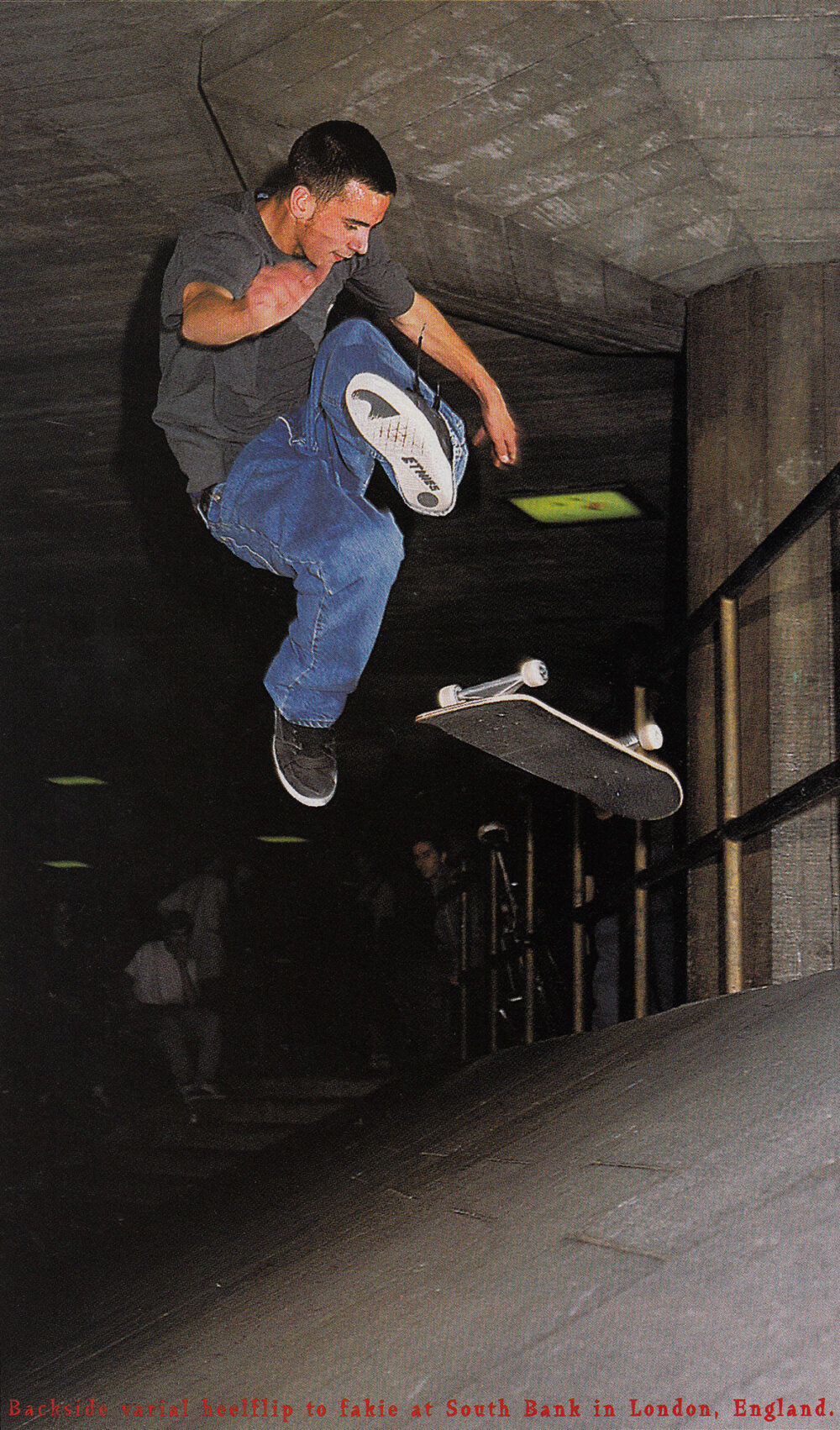

I shot a lot with Carl Shipman. I shot Carl’s (Transworld) Spotlight and I did another thing for R.A.D. with him. I’d go out with Simon now and again… everyone really, a lot of the Southbank kids, Ben Jobe, (Paul) Shier early on.

So you were shooting a lot in London at that point.

Yeah. I’d go up maybe once a month, usually Southbank, but I went to Harrow quite a bit too. I did a big tour in ’93 with Gonz (Mark Gonzales), Alan Peterson and Karma (Tsocheff). That was groundbreaking because it lead to a lot of other stuff. Getting old enough to drive, getting tours, starting to manage a little bit… I didn’t know it at the time, but that was a big stepping stone for what was to come: going over to the States in ’94. That’s when it really went berserk for me. That was a massive step into that really good, early ’90s time in skateboarding. Girl was starting; this seismic shift was happening. We didn’t really know – we were just in it – but it was the next wave.

You started working at Transworld pretty soon after moving to the US in 1994. How did that come about?

I went to the States for the summer in ’89. I went into the office and met Dave Swift and Grant, so they put a face to me. After that, I went over nearly every year, and I’d see them every year at Münster. In ’93, I was doing some stuff for Thrasher, which wasn’t working out, so I asked them for a job, and they were like: “Look, just do a Carl Shipman Spotlight, see how it goes.” That worked out, and then when I went over in January ’94, Steve Berra, who was editor there, was going on to do other stuff, so I jumped in as an editor and senior photographer. I didn’t have the intention of getting a full-time job, but I got one just by being there at the right time. I was in the office getting film – I was already a contributing photographer – and I got the job straight away. That’s when it really took off.

Tell us about working at Transworld in those early days.

It was brilliant. Grant looked at photos with me every morning and we’d shoot every night. We had an in-house darkroom. Photography was such a big thing there. All the editorial staff were good; all the pros were coming in and out all the time. The good thing about that time was that we could pick who we wanted to shoot; no one told us who or what. So if we liked someone, we’d get them in there. It was constant: trick tips, check-outs, interviews or photos for the Sightings. All photos would go somewhere. We were on a bit of a roll then. The magazine went from 94 pages to 400 pages.

People who work in skate media today might find it surprising how much money Transworld was making back then.

Yeah, it was making tonnes of money. The advertising alone… All the skateboard companies would get a deal. We charged more for general ads. That was one of the only ways they could reach that young demographic, though magazines like ours. I think we had 112,000 subscribers and we’d do 50,000 on the stands monthly, so it was a big deal for a while there, and they had a snowboarding magazine, a motocross magazine, a big portfolio of mags.

For younger readers, can you explain a little bit about how a magazine worked back in the analogue days?

Everything was on slide or black and white and would have to be scanned – it was usually done by drum scanner. The black and whites would have to be printed in the darkroom into 5x7s or 10x8s before scanning. There was no digital photography, but the magazine was laid out on a computer. We’d have three weeks to do the magazine, it went away for a week, then we’d have to do this thing called blueline. The blueline would come back, and we’d hand check the typos and the colour. Usually something would be wrong there, so that would go back again. So it took a month, but we’d be two months ahead, and we were always late because there was always something going on. But it all worked out in the end, and the magazine would come in maybe a week and a half later. We’d get the first box, and then two weeks later it would go on the shelf and everyone would get it.

How many people were working at Transworld at its peak?

At the peak, with everyone there, probably 150-180, with all the magazines. The staff (at Transworld Skateboarding) was probably 15-20, more like 25 with the photographers. Two art directors, copy editors, production managers, ad sales… it just goes on. There were probably 50 people on the masthead, but like 20-25 actually working on it full-time.

What did an average day look like for you back then?

We’d be in work at 10, then we’d all leave by two or three to go shoot. Usually we’d be out shooting until eight or nine, then we’d drop the film off on our way back. So they were long days, Saturday and Sunday as well. We were so engrossed in it, I didn’t think about time off or anything else; it was all photos, photos, photos.

So you would drop your film off for processing after a long day’s shooting?

Yeah, we dropped the film off at a lab called Chrome down Del Mar way. You’d fill out the form, put it through the postbox, and it would be in the office the next morning. So we had slides to check every day. There were bricks of film in the fridge all the time. You could pretty much take whatever you wanted, whenever you wanted.

Did you have to change how you shot because of the bright sunlight in California?

Yeah. Grant had this thing: he would not shoot until after three o’clock, until the shadows dropped, so that he could use the fill flash. I didn’t realise they were using flash for the longest time; I thought it was just California light. As soon as you knew the power, the aperture and the shutter speed, it stayed at that; it didn’t really change. Grant was always like: “It doesn’t change. The aperture doesn’t change, the light doesn’t change.” So for me, it always 500 / 5.6 in the day, and then with flash it was always 250 / 5.6. The only thing that changed was the shutter speed; that went down at night. Everyone kept all the numbers a secret, so you had to work it out like trial and error, but Tobin (Yelland) and Luke Ogden really helped me when I first got over there. Tobin was like: “You’ve got to open it up, push the film,” and that was a big help. Pushing film, overexposing everything, that’s kind of the secret to bringing out the shadows, which is the opposite to what you’d think. In a weird way, photography kind of works opposite to how you think it does. The numbers are all back to front. It’s not an easy thing to grasp; a lot of physics is involved.

You went on to become managing editor at Transworld. How did that come about and how did you find that role?

Luck (laughs). I didn’t really want to become editor-in-chief, but all the guys left to do The Skateboard Mag, like 14 people left.

Oh, I see.

I was quite happy being an editor and photographer. It was complicated: we tried, but we couldn’t get anyone to be the (managing) editor, so I jumped in. I took on this managerial role, which, honest to god, wasn’t fun. It split everyone. Harsh decisions had to be made. At that time, we were owned by corporate America, so I was going to New York every couple of months and dealing with all that Wall Street bullshit. It didn’t end particularly well. It was all right for a bit – the magazine was good, it floated well – and then when the social media thing changed, magazines kind of went down the pan. There was the first financial crisis too. It was great for a long time, but when all the money stuff came in and all the clashes started happening, the whole thing changed. It was definitely stressful towards the end, but working for Transworld was absolutely brilliant and I wouldn’t change a thing. When I first went there, Peggy (Cozens), Larry Balmer and Brian Sellstrom ran it. It was full mom-and-pop; it was amazing. You’d get pay rises every year and there’d be money for travelling. When you were staff there, they really nurtured you, looked after you and made you progress in all these different ways. For years there before it sold – it sold in maybe ’98 or ’99 – it grew and grew, and got big in a really nice way.

How did things end at Transworld?

My days were numbered there. I couldn’t put the hours in any more. It was all right – there was no “I’m out of here” – they just laid me off, paid me for a little bit, and then I was working for adidas.

So you started working for adidas soon after?

I was trying to find a way out when all this was going on. I got the TM (team manager) job at adidas in the summer, I think 2012. I’d been at Transworld a long time by then – 18 years, maybe longer.

Am I right in thinking the magazine went out of print around the time you left?

No, it stayed in print. Jaime Owens came in. He was the editor for a while. I can’t remember when they pulled the plug on it. It’s just an ongoing online thing now. I didn’t see the magazine going; I don’t think anyone did. That’s what happens with corporations, when they (magazines) are run from the outside. A lot of people lost jobs, which was sad.

On the subject of digital technologies coming in, I learned from your Brain Drain interview that you struggled with the transition from analogue to digital photography. Can you talk more about that?

I struggled. I mean, I fully have ADHD, so I cannot pay attention on a screen, and I just couldn’t get it looking the way I wanted it to look on the computer. Black and white I could, but I could never get the colour looking like colour slide. And you’re shooting so many photos now – it’s like a digital speed. Before, you had a roll of 36, and hopefully there’d be two on it that worked. It was slower, and to me that was easier. No disrespect to anyone, but I think now, everyone is just shooting the same lighting, and we’re trying to make it look like analogue. We still want it to look like it did in the first place, even though we’re shooting digital. Back when we had analogue, there was more experimentation; we could do different things with film. But analogue’s making a comeback, isn’t it? Film’s coming back, vinyl’s coming back – in a way it’s all going around, which is nice.

How did you adapt to the team manager role at adidas? Did you enjoy it?

It was really good. The travelling was awesome. The crew was amazing. During that time, I helped sign a lot of people: we got Tyshawn (Jones), Miles (Silvas) and Na-Kel (Smith). The signings we did right before Away Days really took it to the next phase of what adidas became. Just meeting all the guys, travelling with them and having access to Mark again was brilliant. Getting to know Chewy (Cannon), Benny (Fairfax) and all the London lot was fun.

Did you get to shoot much during that period?

Yeah, I did. Sem Rubio was the (adidas staff) photographer and I copied his rig. I shot quite a lot of ads, but also a lot of still (life) photography of the shoes, whatever the agencies needed, really. So I had a side thing going as well, which was great.

Jumping back a bit, who were some favourite people to work with during your time in California?

In San Diego who would it be? Who would be down there? (Rob) Dyrdek became a really good friend, and then Kien Lieu, all that Pacific Beach crew. I mean, there were just tonnes and tonnes. (Chad) Muska was really important, because I shot him really early on and kind of went through his career with him, (Tom) Penny when he came over, Jamie Thomas, and then all that surf crew I got access to, the Girl crew, Kareem (Campbell)… Early on, I was with all the Stereo and Real guys, so I shot all that. Maybe not so much the east coast crew, but at one time or another I did get to shoot… I won’t say everyone, but a lot of important teams and people. (Sean) Sheffey was really important to me. Marc Johnson was really important, all that San Jose crew. We had the vert ramp in the Y (Encinitas YMCA) back then, and that was a big hub. (Mike) Crum, Jason Ellis and Tony would be there every day, so we’d be there. A lot of Florida people would come up, like Mike Frazier and John Montesi, and teams would always have riders coming in, like Alien (Workshop) – (Josh) Kalis was there quite a lot.

Were you ever starstruck by anyone you worked with?

I was only starstruck by people from the ’80s, people like Tony; I’d always have trouble talking to Tony. Not Lance and Cab; I became good friends with them. When you get a “Happy father’s day” from Cab, you’re like: ‘Yes! I’ve made it.” Stuff like that was really cool. Those old school guys were just proper gentlemen.

Do you have any good Muska stories, perhaps linked to a favourite photo?

There are so many. What I do remember about him though, is that he would go and skate anything. I have this one photo of him on this rail, no filmer. This rail has got to be 40 or 50 stairs – massive – and he just jumped over it and slid and rolled. That’s what he was like: really spontaneous. He was always down to go skating and he never complained; he’d take a bashing. He was just really good fun to shoot. And he became The Muska, enigmatic. He became a super star, which was amazing. I was there through all that, shooting his video parts and all that crew. Penny was a big part of that scene. They lived together, so they were together the whole time. Chad got everyone together, got the scene going. He was really motivated, but he got a lot of other people motivated as well.

Do you have any good Penny stories? A memorable session or favourite photo…

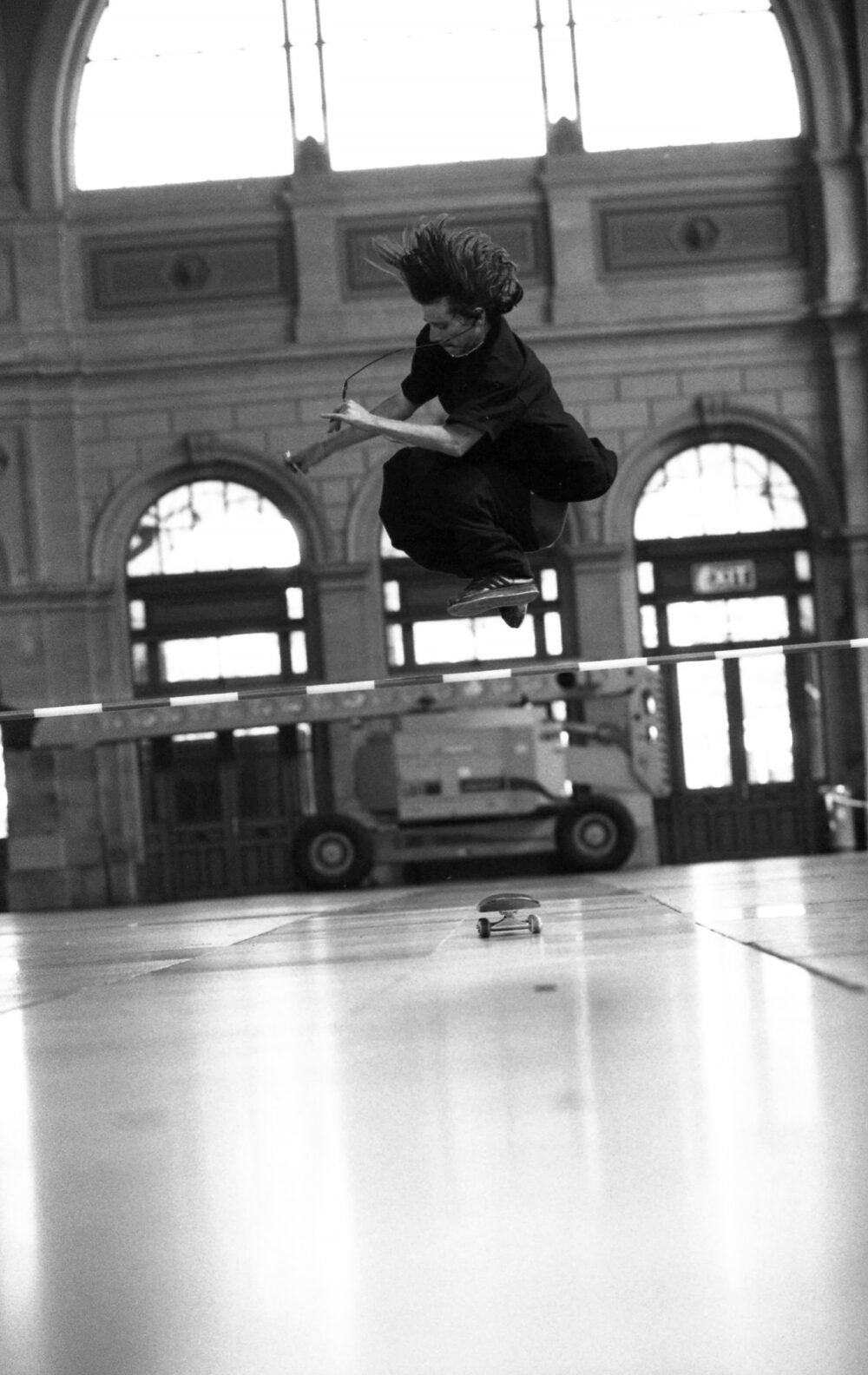

The one that’s in the show is the 360 hippy jump. I think he’d been gone for two years before he came on that Circa tour. I always remember that.

Was that the Video Radio tour?

Yeah, Video Radio. He did the nollie hardflip too. He was living in France. I don’t know how much skating he’d been doing; probably quite a lot, knowing Tom. He was in Paris – I think he was just there by default – so we just grabbed him and put him on tour. It was brilliant to see him again. Video Radio was a brilliant trip. All the stars aligned.

That was peak Muska fame.

Yeah, like crazy. I’d been gone for two or three years – I came back to Britain – so to see him going to the super star that he was and all those guys, – Jamie as well – was nice. It was good to be part of that group through Circa. That was another relaunch for me, really. Through Circa, I got access to a really good core of the new group.

Am I right in thinking the hippy jump photo was shot inside a train station?

Yeah, I think it was in Milan. No one knew he was doing it. He was just rolling around and started jumping over this police tape. That was Tom, you know? He wasn’t like: “I’m going to do this”, he just started. That’s one of my favourites of Tom.

What about the Girl crew? How was it working with them? They were a pretty elite crew.

Yeah, they were. Jody Morris was shooting them, maybe a couple of other people were, but nobody was really in LA shooting those guys. I met Rick (Howard) in the summer of ’94 on a European tour and I was like: “Oh, I’m there (in California),” and he said: ‘Just come up.” I would go up and meet those guys every weekend, pretty much, maybe in the week as well, and through that I got access to Guy (Mariano)… well everyone, really. I got a lot of stuff with Rick through it, loads of stuff with (Eric) Koston, but not much of Chico (Brenes) or (Tim) Gavin. And I travelled with them too; we went to New York. We became good friends. Megan (Baltimore), who runs it (Girl), was brilliant. She really took care of me. So did Dan Field, who was a big part of that family. There were a lot of good times: lots of travelling and loads of good skateboarding.

What video were they working on at this point?

Mouse. I shot a couple of Guy’s tricks in there. I went in and saw Guy’s part early on, and that was mental, like: “Oh my god.” That part is still groundbreaking today. They showed me all Spike’s skits before they went in as well, so that was amazing.

Who were some skaters who were harder to pin down, but worth the effort?

Guy Mariano. He was really hard to pin down, but brilliant. I shot a bit of Kareem, but he was really busy and hard to get. All that LA crew, and I’d say specifically the Lockwood crew, were really hard to get into. All of SF was accessible to an extent, San Diego was, but I think LA was definitely a breed of its own. I think everyone just skated and really didn’t think about getting an ad because it was all in its really early days of what it was about to become.

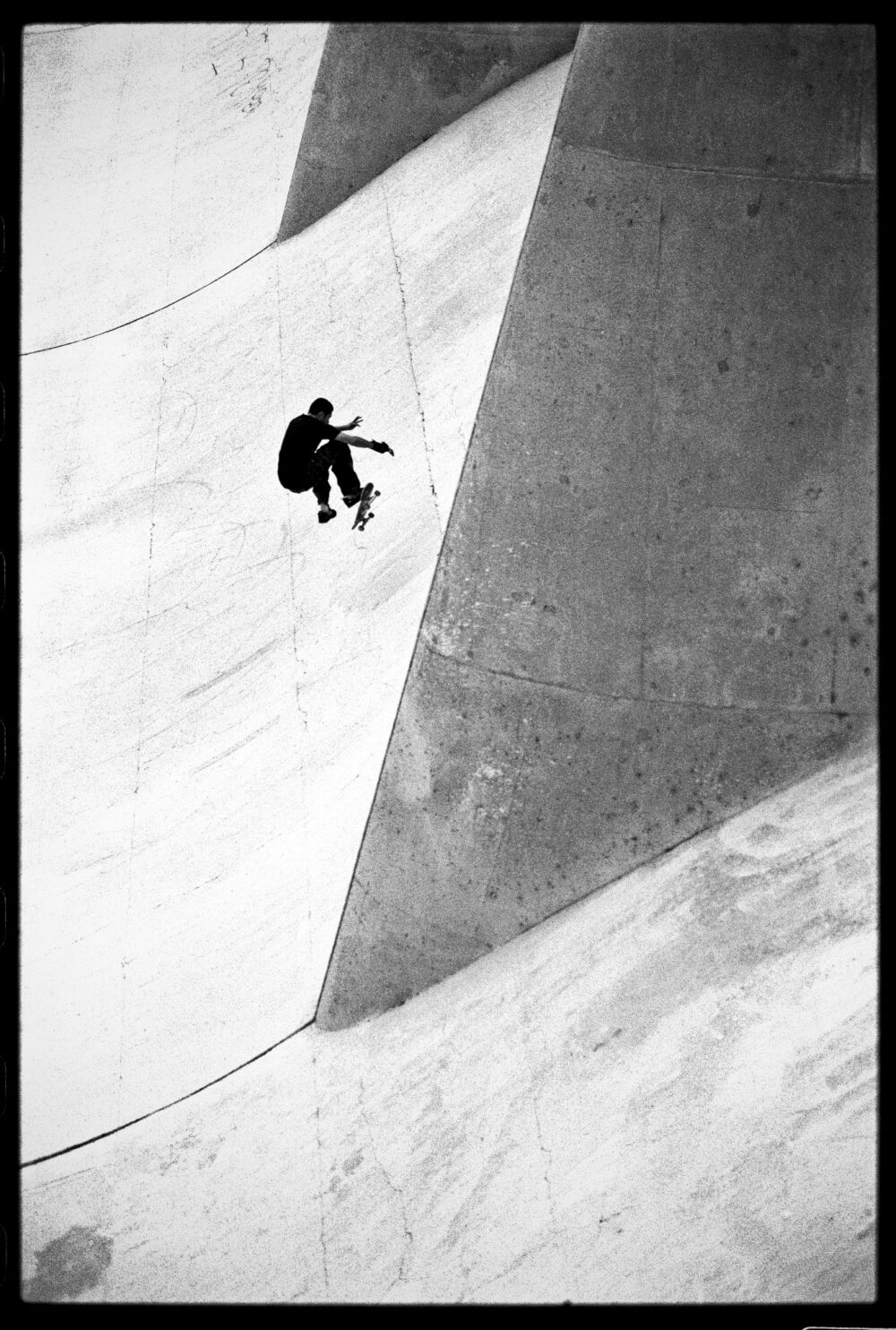

That makes sense. You mentioned in your Brain Drain interview that your photo of Josh Kalis at the Golden Gate Bridge is your best-known photo, but I wondered if you have some personal favourites from your time in California, based on the images themselves or the stories behind them?

I like a lot of the Gonz stuff, just because it’s Mark. I really like some of the pool and vert stuff I shot too, looking back. I always loved shooting vert. A lot of the stuff I’ve been doing now has been shooting vert again. I just like the way skateboarding looks in pools and on vert, and it’s really easy to shoot compared to street. That’s a hard question. There are so many. When I did the show at Glynn Viv, they curated it, they picked everything, which was really nice because I wouldn’t have done any of that. And that’s not even one per cent of it. There’s so much more here that people haven’t seen.

In your Brain Drain interview, you spoke briefly about how you felt about your biggest body of work, which was printed in Transworld, not being accessible today. I found this really interesting. Can you talk more about this?

Well luckily I kept the copyright of everything, so I have pretty much everything here, but it’s hard. The (Glynn Vivian) show was a really nice way of getting part of it out, and Neil McDonald’s been brilliant; he came down and picked some stuff for his book last October, and that really helped me come out of my shell and actually get going again. What TLB did with that book (Read and Destroy) is great, and Grant’s book too. I think there needs to be a book, really. There’s so much work, but it doesn’t sit anywhere; it’s just in boxes. There’s an idea to do a website and get them all scanned, but I’d be looking at the computer until I was dead by the time it was all done. It will come out some way. I’m actually moving offices now, and I’ll go through my archive properly and actually really try and put it into some kind of alphabetical order, and start getting it all scanned. I’d like to do maybe one book, but I’d like to do more books that are editorial and work with different people, not just me. I think that as we get older, more people are interested in the heritage of skateboarding and the stories before, more so than the stories that are happening now.

Would it be fair to say you took a step back from the skate scene for a period?

Yeah, well I was diagnosed with bipolar (disorder) six years ago. I had a breakdown in America, lost my shit – not for the first time – and then I was like: “I’ve just got to come back,” because of the NHS. Luckily I bought a little place here, so I didn’t have so much stress with money, but I couldn’t look at photos for a long time. It (Skin’s archive) was sitting there. And Covid didn’t help; we all got really reclusive. It’s only now, with the show and Neil and just going out and seeing everyone again… it’s been brilliant. I went to that Dean Lane contest (DLH Hardcore Funday) and fucking hell, it was mental. There were at least 2000 people there; it was unbelievable. The scene is just thriving. It was really nice to see.

That’s good to hear. So where are you at with managing your diagnosis?

It’s a constant thing at the moment, just a constant awareness of it. I have a social worker who’s really good, a doctor I check in with and I’ve done therapy. If I’m struggling, I just make a call; I’ve got a good network of friends. I try not to look back; I just go forward as much as I can. Getting out of bed – that’s a win, cup of tea – that’s a win. For sure there might be losses in the day, but there are all these little wins. I learned cognitive behavioural therapy as well, which has helped quite a lot. Everything leads to something, and with this behavioural therapy, you stay a step away from that. So, for example, if I go to that pub, I’m going to get into a fight and that’s going to be a problem, so I don’t go to that pub. I try to stay two things away now. I know what Swansea’s like; there’s always something going on. Every day, you’ll see a fight or something, so I walk away from the pub and if someone talks to me, I cross the road and walk away. I just do not get involved in anything that can lead to an anger issue. That sounds really fucking easy, but that’s the cognitive behavioural therapy.

Another thing that’s been really good is that because I’ve been talking about my experiences, loads of people have been reaching out and I’ve been trying to help as much as I can. Luckily, people are talking about mental health more and more now. I’d say this to anyone who’s struggling: just talk to someone because bottling it up is not going to lead anywhere good. The first thing is to try to help yourself, really. And the people in the NHS are amazing. If you go to hospital for it, there’re there to help you. You can get yourself down worrying about going to hospital, you know: “I’m doing this again,” but they’re there to make you get better. All that stigmatism that we’re used to with mental health is not there at all. There’s one-on-one nursing there for you, there’s help, there are things you can do.

Thanks for talking so openly about that. So, on to your exhibition at Glynn Vivian – how did that come about?

Well, Karen MacKinnon, the curator and boss of Glynn Viv, is a friend of mine. I’ve known her since we were 14. We were trying to do a show on skateboarding, which didn’t pan out, and she said: “Look, we’ll just do a show on you.” That’s what happened. I edited it in about a month. I took out all the sheets, took them to the gallery, and they edited them again. The good thing is, there’s classic stuff in there, but there’s also archival stuff, contact sheets, stuff I brought from Transworld that was going to go in a skip. So there’s a bit more to it than just photos. It’s more like an installation than a photo show. It came out really good. The space is amazing. The reception’s been really good. The opening night was great.

People traveled from all over for the opening.

Yeah, people came from everywhere, which was really nice. There were like 200 people at the opening, a really good turnout; people were stoked. It was just a nice get-together, really, a nice reminisce, much like the R.A.D. weekend – everyone hanging out again, which we don’t do any more in skateboarding. We should. We all used to hang out at contests. But it was the start of something, which is good. We’ve got a million pounds here from the council to build parks, so hopefully in the next couple of years, Swansea will really become what it once was. Fingers crossed.

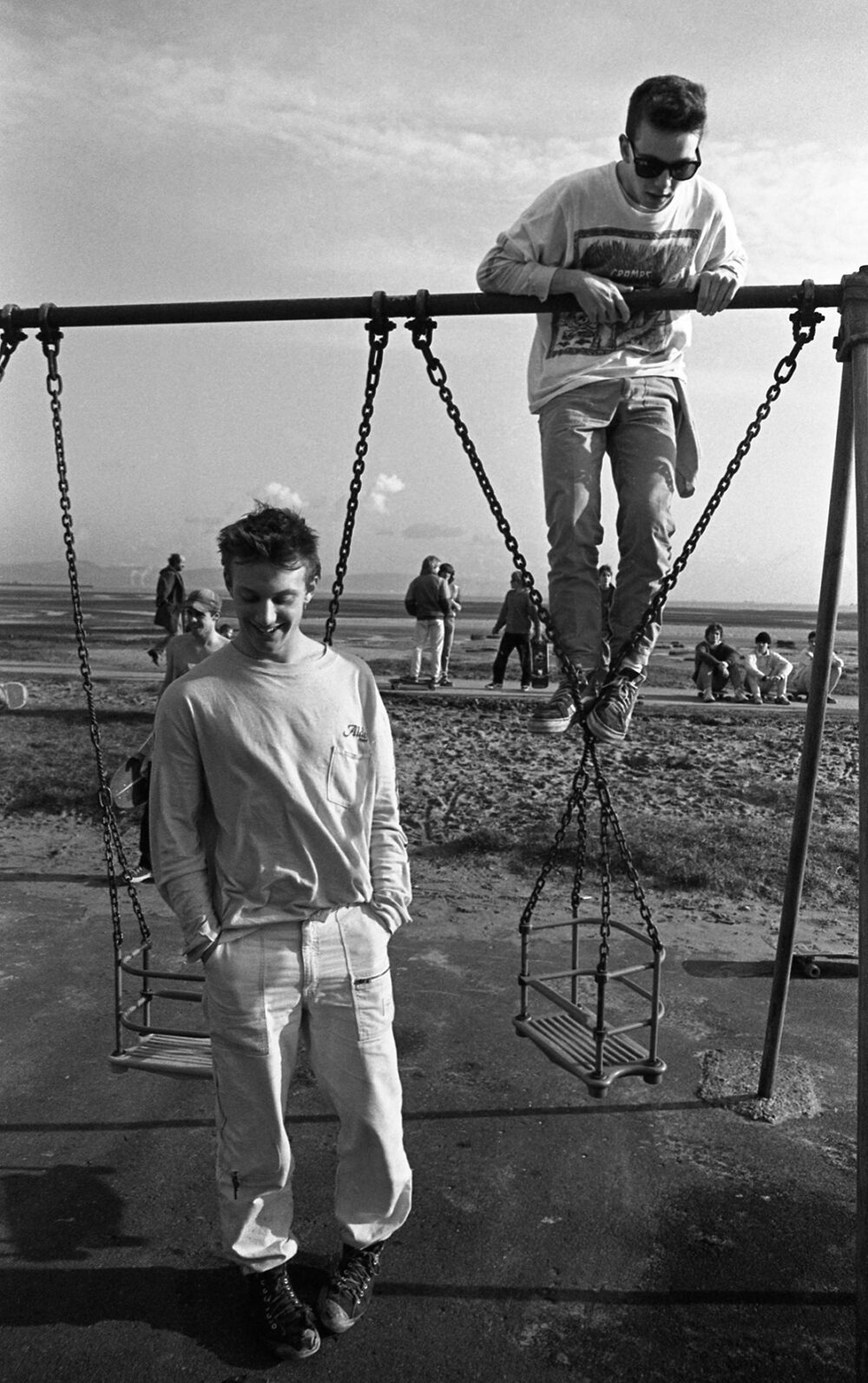

There are quite a few documentary photos in the exhibition, in addition to more traditional action shots: bleak, wintry shots of old ramps and groups of local skaters hanging out. Some of my favourite photos in the Read and Destroy book are similar. They are really evocative of a time when skateboarding in the UK was tiny, and the juxtaposition of huge ramps with wintry British countryside, for example, is really interesting.

I think that’s because at some point it goes from skateboarding into social history. I love all that stuff. With those type of photos, it’s always just: “I remember doing that, I remember building that ramp.” There was that ramp in the woods, the (Derwyn) Fawr ramp, which was really amazing for the time, but now looks really ramshackle, and we would go in the woods and skate that. They were really rough, badly-made ramps, but they were our ramps and they were where people learned their trade. They look like pieces of art to me now. Looking back, they were the salad days and you think: “Oh my god, it would be great to do that again.” No one gave a shit in the ’80s: wacky haircuts, the graphics were amazing, the skateboarding was incredible. The music scene? Not so much, but skateboarding in the ’80s was just an absolutely brilliant time.

There are some photos in the exhibition that were shot this year. Tell us about those.

Those were commissioned works, so that got me out. I shot Sam Pulley, who came down for the day, and this other guy, Hass (Hasan Kamil). The gallery bought those photos, so that worked out really good. It was just nice to be photographing again and getting out, doing it. I’ve been doing bits of band stuff too, bits and bobs.

Are you planning to shoot more skating?

Yeah, I’ll be shooting more and more now, for sure. New Balance was brilliant, they helped me out with the show. I’ve got to give (Dave) Mackey a shoutout; he’s been a diamond. I’m going to Madrid with New Balance to see the premiere of a new video coming out at the end of October, and then I’m planning to go back to California over Christmas to see my son. Baby steps.